This is the second post in a series by Meghan Rubenstein. Read her first post here.

A couple of nights last week it was so cold in Santa Elena I slept in a ball in my hammock. Although it probably didn’t drop much below 70 degrees, it was noticeably cooler than the previous weeks. The change in temperature was brought on by a frente frío, a cold front with precipitation. For about a week, the afternoons and evenings have been punctuated by intense thunderstorms. During the day the temperature still climbs above 90 degrees—and work at Kabah continues.

I just completed my fourth week with the archaeological project. Since the first week at the site, I have taken on some new tasks. In addition to registering stones, which I explained in the previous post, I have started to assist with schematic plans—scale drawings that record the location of each stone and artifact uncovered during the excavation. A couple of days I tagged along with the survey crew, who introduced me to new sectors of the site. Sometimes they had me call out coordinates or locate the next marker. I was also asked to clean and draw a section of stucco on an interior wall of the Codz Pop, which had traces of Maya graffiti.

In my free time, I worked on building my image archive. I circled the Codz Pop taking photos of all the scattered fragments of the façade piled around its base. Some of these carved stones were moved to their current locations 65-100 years ago, and others even longer. The stones without archaeological context cannot be reintegrated into the façade, as their original placement is uncertain. However, knowing they were once part of the building design still provides valuable clues for my analysis.

A couple of weeks ago, I also had the chance to travel with project members who were documenting the conservation work completed earlier this field season at several neighboring Puuc sites. At Labna, Sayil, and Xlapak, they walked me through the steps archaeologists and conservators are taking to protect Maya buildings from moisture, aggressive plants, and erosion. Some of the work is also corrective. In the past, cement was used in architectural restoration. Now it is known to cause considerable damage to the integrity of a structure, allowing water to leak in and destroy buildings from the inside out.

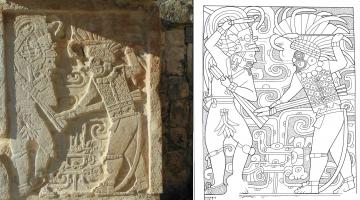

Similar conservation is also taking place at Kabah. On a trip to the far western sector of the site to check on this work, I was able to visit a structure at Kabah I’ve never been to: Manos Rojas. Seeing this building was especially exciting for me because it is a unique, richly ornamented example of Puuc architecture. It is buried in the trees and not open to the public. As you can see in the image above, its architectural sculpture is similar to the Codz Pop (note the use of the "mask"), but it is executed in a different style.

I’m not sure if it is a coincidence, but with the change in weather I started to feel less exhausted. The first month, I returned home every night with my head spinning. This week I spent more time recording research notes than words and phrases to remember. I even found time in the evenings to hang out with my neighbors. I have become accustomed to life here more quickly, and more easily, than I thought I would.

We worked through Saturday this week. On Monday we return for the final days of the field season at Kabah. Then, I will turn my full attention to my own research.

This entry is part of a series by Meghan Rubenstein documenting her fieldwork in Mexico in 2012 and 2013. Because the entries are taken directly from her personal reports created in the field, they refer to the work being undertaken in the present tense.